Application architecture with Datomic: branching reality

- Universes

- Lemma: mocking Datomic connections

- Forking universes

- About mutability

- Forkability, and Clojure's time model

- Practical usage

- Parting thoughts

In this post, I'll present an architectural pattern for structuring Clojure and Datomic apps, playing a similar role to Dependency Injection in the Object-Oriented world.

The big picture is that your application logic manipulates universes, which are mutable programmatic values with a fork operation, which essentially makes 2 diverging universes out of one. This 'fork' abstraction is analogous to forking branches in Git, and is made possible using one of Datomic's special powers: speculative writes.

I've found this approach to make system-level tests very straightforward to write, and to play nicely with interactive development. Read on for more details.

Universes

Any but the most trivial application needs some way to separate configuration from use. Some examples:

- if your application is backed by a database, you'll want your application code to use a connection to your test database in a test environment,and a connection to your production database in a production environment.

- if your application needs to send emails, for instance using a web service like Mandrill, you'll want to use a test Mandrill token during development and tests, and a real Mandrill token in production.

These requirements are well-known, and have been traditionally addressed in class-based languages like Java using 'Inversion of Control Patterns' like Dependency Injection and Service Locator.

In Clojure, there are no classes, so it's tempting to simply use global Vars to store configuration:

(require '[datomic.api :as d])

;; configuration

(def conn "the Datomic connection"

(d/connect (System/getProperty "DATOMIC_URI")))

(def mandrill-token "the token for authenticating to the Mandrill API"

(System/getProperty "MANDRILL_TOKEN"))

;; business logic

(defn some-business-logic [x y]

(d/transact conn (make-some-transaction-using x :and y ...))

(send-mandrill-email! mandrill-token (make-some-email-with x :and y ...)))

Please, never do this. This is global state and environment coupling at the same time. It will make your tests harder to write, ruin your REPL experience, and complect the lifecycle of your application with the loading of its code. Bad, bad, bad.

Another tempting idea is to use dynamic Vars, one of Clojure's special features, to mitigate the above-mentioned issues:

(require '[datomic.api :as d])

;; configuration

(def ^:dynamic conn "the Datomic connection" nil)

(def ^:dynamic mandrill-token "the token for authenticating to the Mandrill API" nil)

;; business logic

(defn some-business-logic [x y]

(d/transact conn (make-some-transaction-using x :and y ...))

(send-mandrill-email! mandrill-token (make-some-email-with x :and y ...)))

;; starting the application

(defn start-app! []

(binding [conn (d/connect (System/getProperty "DATOMIC_URI"))

mandrill-token (System/getProperty "MANDRILL_TOKEN")]

...))

I don't recommend this either. This is still environment coupling, even if you have an easier way to control the environment. You may also find yourself typing thse annoying (binding ...) clauses all the time in the REPL, which kind of defeats the purpose of using Vars.

It is now an established best practice in the Clojure community to pass the configuration as additional arguments to your business logic functions, making them self-contained. For example, you can pass the configuration values as a map

(defn some-business-logic [{:keys [conn mandrill-token]} x y]

(d/transact conn (make-some-transaction-using x :and y ...))

(send-mandrill-email! mandrill-token (make-some-email-with x :and y ...)))

Where does the configuration map come from? It depends on your application. For instance, if your application is an HTTP server with a Ring adapter, the -main function could create the configuration map from environment properties at startup, then listen to the HTTP port and 'attach' the configuration map to each incoming request.

This 'configuration map' could also be called a 'context' or 'environment', but I want to call it a universe, for reasons which will become more obvious later.

What makes a universe? Here are some examples of what you might put in this configuration map:

- database connections

- API tokens and other configuration constants

- application services as protocol implementations (so that you may mock them), e.g Ring session-stores

- if you're using Datomic, the current database value

- the present time (never use

(new java.util.Date), that's environment coupling too!)

The mental model is that your application logic is made of stateless, configuration-free, timeless components which manipulate the universe (any universe) in response to events. In contrast, with Dependency Injection, I would say that your application components are created inside and configured by a universe.

In testing, universes will tend to be made out of test database connections and mocked services. After all, that's the idea behind making mocks for testing: fabricating a small, isolated universe in which we can mess around without affecting the real universe, the one our business cares about.

Hold that thought. We'll make a small detour in Datomic Land to get some reality-branching superpowers, then come back to universes, at which point things will get more interesting.

Lemma: mocking Datomic connections

Datomic supports speculative writes, in the form of its datomic.api/with function. Roughly speaking, with accepts a database value and a write specification, and returns an updated database value as if you had sent a transaction to the connection.

Therefore, it's useful to answer "what if" questions. But we can go further and abuse with to mock Datomic connections in-memory. Here is a complete implementation, which is essentially an Atom holding database values, which uses with for writes (edit: you can now use the datomock library):

(import 'datomic.Connection)

(import '(java.util.concurrent BlockingQueue LinkedBlockingDeque))

(require 'datomic.promise)

(require '[datomic.api :as d])

(defrecord MockConnection

[dbAtom, ^BlockingQueue txQueue]

Connection

(db [this] @dbAtom)

(transact [this tx-data] (doto (datomic.promise/settable-future)

(deliver (let [tx-res

(loop []

(let [old-val @dbAtom

tx-res (d/with old-val tx-data)

new-val (:db-after tx-res)]

(if (compare-and-set! dbAtom old-val new-val)

tx-res

(recur))

))]

(.add ^BlockingQueue txQueue tx-res)

tx-res))

))

(transactAsync [this tx-data] (.transact this tx-data))

(gcStorage [this olderThan])

(requestIndex [this])

(release [this])

(sync [this] (doto (datomic.promise/settable-future)

(deliver (.db this))))

(syncExcise [this t] (.sync this))

(syncIndex [this t] (.sync this))

(syncSchema [this t] (.sync this))

(sync [this t] (.sync this))

(txReportQueue [this] (.txQueue this))

)

(defn ^Connection mock-conn

"Creates a mocked version of datomic.Connection which uses db/with internally.

Only supports datomic.api/db, datomic.api/transact and datomic.api/transact-async operations.

Sync and housekeeping methods are implemented as noops. #log() is not supported."

[db]

(MockConnection. (atom db) (LinkedBlockingDeque.)))

You may be wondering, how is this different than using Datomic's built-in in-memory connections ? (as in (d/connect "datomic:mem://my-db-name"))) Well, Datomic's in-memory connections start with a blank database, whereas in the above implementation the user provides a starting-point database. This starting point might be a database loaded with fixture data; it might also be your current production database!

In particular, you can use these mock connections to make a local 'fork' of any Datomic connection:

(defn ^Connection fork-conn

"Creates a local fork of the given Datomic connection.

Writes to the forked connection will not affect the original;

conversely, writes to the original connection will not affect the forked one."

[conn]

(mock-conn (d/db conn)))

Analogy to Git: This is the same notion of forking as in Git, where database values are like commits, and connections are like branches. (However, unlike Git, there is no 'merge' operation).

Forking universes

This notion of forking is interesting, and applicable to other objects than Datomic connections. For example, immutable data structures and simple mutable interfaces (e.g HTTP session stores) can be forked too.

Which brings us to the main point: if the universes of your application have Datomic as their main data store, then you can fork these universes.

Forking a universe is making a local 'copy' of a universal which behaves exactly as the original one, in which you can mess around without affecting the original one.

This is of tremendous value for system-level testing. Because of functional programming, Clojure already has a great story for testing in the small, but in the large, your system is essentially a process which performs in-place updates in response to events. Forkable connections are a nice fit for this model. Forget about your setup and teardown phases: instead, you have a starting point universe, and for each of your tests which involves writes, you simply fork off another universe, perform your tests, and forget about it when you're done. Garbage collection will do the cleaning up for you.

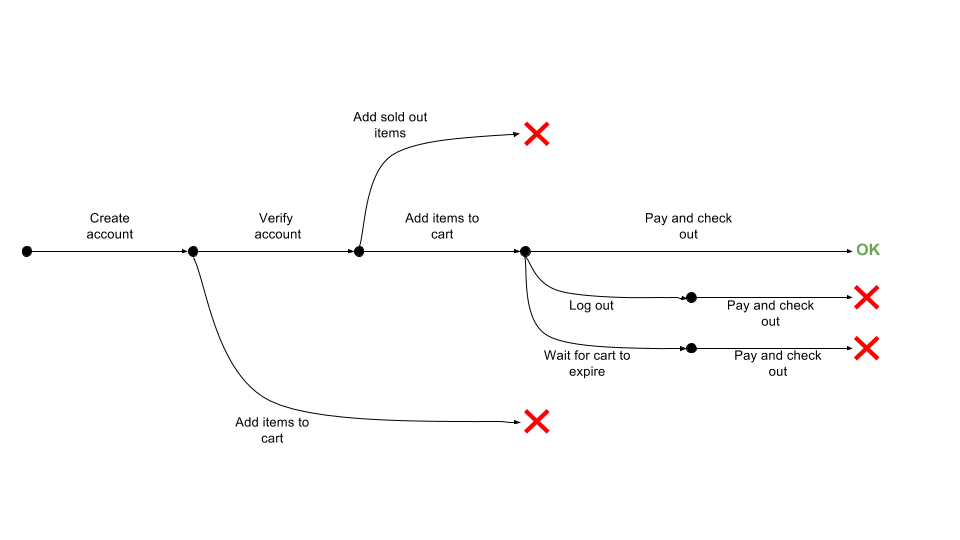

For instance, imagine you have an e-commerce website, and you want to test the purchase flow. The purchase flow consists of the user signing up, verifying her account, adding items to the cart, and checking out. Typically, the test will consist of one ideal scenario, and several scenarios where things go wrong, like the cart expiring or the user logging out before checking out. You can easily test this by branching off several universes matching different scenarios as you progress along the user path:

The code for testing this may look like the following:

(let [u (fork starting-point-universe)]

(create-account! u)

(let [u (fork u)]

(expect-to-fail

(add-items-to-cart! u some-items-data)))

(verify-account! u)

(let [u (fork u)]

(expect-to-fail

(add-items-to-cart! u sold-out-items-data)))

(add-items-to-cart! u some-items-data)

(let [u (fork u)]

(expect-to-fail

(log-out! u)

(pay-and-check-out! u)))

(let [u (assoc (fork u)

:now (after-the-cart-has-expired))]

(expect-to-fail

(pay-and-check-out! u)))

(expect-to-succeed

(pay-and-check-out! u))

)

Forkable universes also offer a lot of leverage of interactive development. Sometimes I want to work in my development environment with my production data, but without committing any change to my production database; this is useful for experimenting with new features, or for demonstration purposes. All I have to is fork my production context and run my local server on it.

I can also imagine automating the above idea to make "inspection tests", in which you would periodically simulate some scenarios on your production data.

Finally, I think forkability makes room for some REPL-friendly debugging techniques. For example, you can insert 'checkpoints' in a code path you're debugging, which when reached will make forks of the current universe and store them. You can then retrieve these checkpoints to inspect the past of the universe, or to replay some steps manually.

About mutability

Universes are essentially about mutability and side-effects, which may seem at odds with the functional spirit of Clojure and Datomic. That's not the case in my opinion, since Clojure positioned itself since the beginning as supporting mutability in the few places where it is a better fit than a purely functional style.

Having said that, universes and the ability to fork them are no excuse to make a mutable imperative mess. You still want to make the building blocks of your application purely functional, on as large a scale as is reasonable.

Forkability, and Clojure's time model

The Epochal Time Model embodied in Clojure and Datomic consists of an identity (represented e.g by a Datomic connection, an Atom, ...) which state changes over time as a succession of values (e.g Datomic database values, persistent data structures, ...): "the state is the value of an identity at a point in time". In this model, changing the state means setting the state of an identity to a new value.

Interestingly, forking also has a natural interpretation in this time model: duplicating an identity without changing its state. (at least that's the way I see it).

Practical usage

I have a test namespace with a function to create 'starting-point universe' loaded with fixture data. This function is called by tests, and by me from the REPL. Because loading the database schema and fixture data can take some time (~100ms), I back this function with a TTL cache of a few seconds. This allows me to never have a stale context as my code evolves, while not wasting time on a heavy setup phase for each test.

On top of that, I have a dev namespace with 2 functions fu (Fresh Universe) and lu (Local Universe). Both return universes with fixture data, but fu returns a different universe each time it is called (stateless), whereas lu creates a universe the first time and then returns it (session); there is an optional param to reset the universe returned by lu.

To achieve full universe forkability, I also had to make mock implementations of a few key-value stores in addition to Datomic, such as Ring session stores.

Parting thoughts

I am constantly amazed to see how immutability, although it encourages functional programming, also makes dealing with side-effects and mutable places better. This is a lesson we have learned in the small with Clojure's references, and now we're learning it in the large with Datomic.

At BandSquare we have applied the above ideas to our whole backend system, to great benefits so far. We will continue to explore the possibilities and limitations of forkable universes, and we welcome your feedback.

Happy New Year!